Planning for the future manufacturing of a defined volume of any product should logically involve a projection of the probability of being able to get, during the required time period, the critical raw materials necessary for that manufacturing . Yet up until the 21st century such probabilities were considered to be trivially based on the manufacturer's financial ability at the future time designated. If its finances and credit rating would be strong enough to order the raw materials to be delivered at the point in the future when the manufacturing process would require them then there was no problem, it was assumed.

The actual supply of natural resources was assumed always to be only a function of the price a willing buyer was able to pay to a willing seller. It was further assumed that an increase in demand would always cause an increase in supply.

The hidden assumption was, and is, that the supply of natural resources is infinite.This is demonstrably not true.

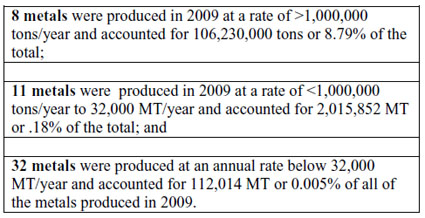

Each year, I quantify the global production rate for all metals to illustrate the thesis that rare metals can be defined by their position in the list of all metals produced when their place in the list is measured by their production rate during that year. A threshold is defined for rare metals by production rate in 2008, for example, as 25,000 MT/annum. By that definition, lithium was the threshold rare metal. Interestingly, it happened that in 2009 lithium production dropped to 18,000 MT/annum., and that there was, in fact, no threshold metal at 25,000 MT for 2009. Therefore, the rare earth metal lanthanum was used for the 2010 chart as a threshold metal with its estimated-by-the-USGS-production in 2009 of 32,000 MT/annum. Lithium production in 2009 dropped well below that of silver and cadmium; and I think this is an excellent example of either a lack of logical future planning if our world policy is to electrify our motor vehicle fleet and store electricity from wind and solar production—or it is an example of the inexorable workings of the law of supply and demand.

Resource production, it must be noted, is much easier to reduce than to increase. Mining and refining involve time-consuming processes and equipment and operations that do not lend themselves to start-stop agendas.

The worlds of finance and politics seem totally mislead by the production of iron ores , pig iron and raw steel. Iron is the most commonly produced metal and the most produced metal in all human history. Of the 1,206,800 tons of metals produced in total in 2009, 1,100,000 were of raw steel; they accounted together for 91.02% of all metals produced.

This fact has blinded completely the global attitude towards the production of metals of all types. It is trivially considered by financiers and planners both public and private that all metals are commodities like iron and can be produced in their current quantities indefinitely. This is not true.

Note that in the next tiers, below iron, in the table:

I define that 0.01% of the metals produced in 2009 as the rare metals of 2010.

Note also here that the list of 32 rare metals includes 12 of the rare earth metals along with yttrium, scandium and thorium; it does not include cerium or lanthanum, which were produced at a high enough rate to place out of the rare metals as defined here.

The world's production of metals has increased dramatically in the 21st century, but the increases have become noticeably unlinked because most of the rare metals used critically for today's technologies are produced only as byproduct races' found primarily in the eight nonferrous metals that were produced in 2009 at a rate of 1,000,000 MT/annum or more. Even the two metals in the not-so-rare category that are of importance to the REE-based technology world, cobalt and lanthanum, are themselves mostly found as byproducts of either nickel or iron mining today.

The resources of all of the rare metals are qualitatively, as well as quantitatively, different from those of iron or the lesser base metals. As grades of the ores of their source base metals decline so must the production rates for the rare metals. There are always exceptions to this rule, but they prove the point rather than disaffirming it. Economics is the main driver for additional resource production, so that if a resource can be produced but no one can afford to use it at that economic point it will not be produced. Natural resource production is also limited by the accessibility of the mineral to be mined, the level of infrastructure available or possible at the otherwise accessible site, the level of technology required to extract the resource and refine and fabricate it for use and the length of time that capital must be tied up without any return—the supply of capital like the supply of energy has practical limitations always.

Limited resources means resource allocation. Some of the formerly weak economies that used natural resources as a piggy bank, such as China, are quickly evolving into economic powers and have crossed an economic threshold point beyond which their demand for natural resources has or can and will quickly surpass their domestic supply.

This has already resulted in the REE-based product industry moving to China to elevate the probability of success of obtaining supplies of critical raw materials to acceptable levels. This is due to the facts that China today is the producer of more than 95% of not only the rare earth minerals and metals themselves, but also all of their fabricated and alloyed forms for end uses. This has, by the laws of simple economics and of allocation, moved the majority of the jobs created by the production and use of the rare earths to the Peoples' Republic of China.

Allocation has been underway for some time in the resources of the rare earths as has the movement of the entire supply chain for rare earth-based end-use products, such as magnets, to China.

Will There Be Allocation of End-Use Products?

Yes, unless the entire supply chain—or a smaller clone of it—is relocated or restarted outside of China and Japan. This supply chain building or rebuilding however is a long-term planning decision based on political, as well as economic, factors. Western economies political future planning is made almost entirely on military-need projections not domestic economic ones.

This is how and why a small military demand for rare earth magnets has been magnified by stock market promoters into a 'crisis.' This promotion is an attempt to substitute critical-for-national defense for critical-for-green technologies, so subsidies can be obtained at all levels in the supply chain (including the first step, mining). This has not been necessary so far for subsidies for green technology, though it may soon be clear even to politicians that having all of the cooking pots in the world is no substitute for having something to cook and something to heat the pot.

This stock market price-driven promotion may turn out to have been a mistake because it gives China legitimate diplomatic reasons on the international stage to allocate; and so, in the end, allows the wrong headed logic of price as the sole demand driver to continue as the basis of long-term planning by governments.

The problem is not self-correcting as market theorists tell us because the development of a mine is the economic antithesis of a reasonable return time on the use of capital. This is why it has always been unpopular with institutional investors dependent on their own money raising on a promise of a quick return.

Only governments can subsidize long-term capital projects, such as mining, energy production or the exploration of space. Only war or the threat of war can force large amounts of public capital rapidly to projects like the devlopment of solid-state electronics, jet aircraft, alloys, nuclear technology and the exploration of space.

Chinese economic issues, the potential for commodity price inflation and the relative value of its currency, are keeping the prices of the rare earths low. The conundrum is that Chinese production until now has been too high, so that it tends to lower the price not raise it in any case.

But lowering production rates is antithetical to the Chinese ethos, inherited from the past, that increased production is the goal of every program.

Production outside of China will, first of all, smooth the world's supply—not decrease it. Only if production occurs outside of china and production inside of China decreases will there likely be a chance of increased prices. Thus, there are already far too many REE projects in the West. They are, in fact, self-destructive. A large increase in LREE (light rare earth) production will drop the prices of Nd; a large increase in production of HREEs will drop the prices of those REEs used in magnets, dy and tb, and destroy the value of, and thus the driver for, investing in the balance sheets of the HREE (heavy rare earth) miners ready to flood the world with HREEs.

The driver for REE production in the West must always be actual demand, but increasing demand in the civilian sector (the overwhelming majority of such demand) is coming from Southeast Asia to where almost all of the total supply chain has gone. Therefore, the driver for Western production will be Eastern demand.

The solution for Western military supply of the rare earth metals is the recycling, first, of all military scrap and, second, domestic scrap containing high values of the REEs. This can be accomplished trivially and will not impact the majority of the REE market unless it becomes a widely used conservation technique.

Today, August 30, 2010, events in rare earth production world (I drafted this paper in May) have occurred that reinforce my thesis. China has reduced its export allocations for all of the rare earths due to a massive restructuring of its rare earth production industry. The REE production industry will now be consolidated geographically under three state-owned, very large base metal producers. This will manifest itself first as a reduction in output as China's 129 REE miners become groups of subsidiaries of just three companies. Inefficient or hopelessly environmentally or safety-challenged, producers will be shut down. The overheads of efficient producers will be further reduced by combined use of infrastructure. Capital for expansion or new discovery will no longer be an issue in the industry.

There is no clear path for the 79 Chinese comapnies that are processors and refiners of REEs. It is to be expected that some of them will be chosen by the superintending major miners to continue and even expand their service business. Others will either vanish or, under a new mandate, be allowed to export their technology to service non-Chinese sources of raw materials. Whether or not non-Chinese miners can or should take advantage of this new source of REE-preocessing technology is a critical question. If a non-Chinese REE production industry is to exist either to supply the non-Chinese world or to supply China (and perhaps Japan and Korea), then the savings in time and cost by working with Chinese processors could be significant and even determinative of which non-Chinese REE producers are successful.

This issue has even brought a new player into the fray. Toyota has announced that it will JV with an Indian company to process REE ores it obtains either in the marketplace (including India or from the REE mine in development jointly between Toyota and the government of Vietnam in Vietnam). Is this India's first step into the international race to secure raw materials of the REEs? Yes.

In the last three months, China has announced or clarified green initiatives that will vastly ramp up its domestic demand just for neodymium for rare earth permanent magnets (REPMs). This in fact may have been the driver for the reduced allocations of the current production of the REEs in China for export. In any case, the demand for the REEs for REPMs is now going to grow dramatically within the Chinese domestic market.

In the short term, five years or more, there is room in the market for non-Chinese production of light rare earths, such as praseodymium, neodymium and samarium. There is room in the market beginning now for new sources of the heavy rare earths, terbium and dysprosium.

China has immense resources of the light rare earths that can be developed over the next 10 years, but the Chinese exploration industry does not believe that sufficient additional resources of the heavy rare earths can be found or developed, at this time, to meet known future needs.

The race is on for the heavy rare earths. Chinese and non-Chinese exploration companies are aggressively looking at REE mining opportunities that can produce HREEs in such quantity as to justify their production. The open issues are pricing, access to processing technology, the relative value of producing REE metals and alloys at the mine and the survival and/or growth of an independent Western (i.e., non-Chinese) rare earth permanent magnet industry.

The question of whether a vertically integrated prodcuer of REPM alloys can be profitable in the non-Chinese world is close to a practical test. If such an entity comes into existence in the next five years, it will almost certainly prod private equity and perhaps even the U.S. government or the governing body of the EU to subsidize a merger of that entity and a REPM manufacturer so as to secure the supply chain for REPMs.

Of course, this will only occur if a Chinese-, Japanese- or Indian-owned and operated entity, private or governmental, does not beat Western private equity and public finance to the finsih line.

This rare earth issue is not isolated; it is, in fact, the first reorganization of a natural-resource production and flow driven by the transfer of of the center of industrial manufacturing from the U.S. and Europe to Southeast Asia. The unexpeced aspect of this logical devlopment is that the global centers of finance have already shifted East accross the Pacific Ocean. Thus, the gloabl control of the situation has passed to China, Japan, Korea—and soon—India. We in the West can now watch as the global model of securing raw materials and using them to produce finished goods for export, in and from the securing country (the imperialist model), has now been reborn in China. The biggest and most important difference between the trading aspects of Imperial Britain in 1900 and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 2010 is that the internal market of the PRC is so vast that it can absorb, in all probabilty, the entirity of the world's production of the rare technology metals for a very long time before it is saturated and mature.

The challenge for non-Chinese manufacturing industry is the security of the supply of its rare technology metals. If this does not occur, then there will be no non-Chinese manufacturing of industrial items critcally dependent upon the metals that are not available except within, and to, China. The rare earth permanent magnet indusrty is merely caught up in the first skirmish of the 21st century's resource reallocation. Let us pray that, when this reallocation happens with water, energy and food, it is a peaceful reallocation.