By the mid-1990’s, China had become the de facto providers of rare earths to the world, due to an abundance of cheap labor and good deposits of rare earths in China. Coupled to technology development that increased the cost competitiveness of the Chinese industry, manufacturers in practically every other nation were soon shutting down, and buyers were purchasing cheap material from China. Most buyers would have been happy to continue this arrangement indefinitely, but as with many materials supplies coming from China, two problems began to rear their head.

The first problem is not peculiar to China, and occurs in mining in general. Because great mines are finite resources, sooner or later you start to realize that the good times must end, that you are running out of ore to mine. Chinese officials began to realize that reserves were being depleted, and so production quotas were established to prolong the period over which ore would be available. In our opinion, however, the Chinese also realized the truth, that availability of rare earths provides a competitive advantage, and since the Chinese did not want to try to outbid Western buyers of rare earths for their own materials, the ministry in China introduced an export quota system.

The export quota was oddly structured. In spite of their being, depending on how you count them, as many as 16 available and different rare earth elements, used in a wide variety of industries and with varying direct economic value, the quota treated them all the same. Manufacturers in China were essentially given permission to ship a given number of tons of raw rare earth product out of the country in a given period.

Highly processed materials or finished products could leave at will, but less processed materials had to be shipped in the context of the quota. Now, some rare earths such as lanthanum and cerium typically make up 25% to more than 50% of the typical deposits. They are not rare in any sense, and have historically sold for roughly USD$3-$5 per kilogram, in a very pure form. But the quota system that was drastically tightened in 2010 treated all rare earths equally, so a buyer that wanted a ton of cheap cerium oxide to polish glass had to compete directly with a buyer who needed a ton of highly purified europium oxide to use in microscopic quantities to make high-power white LEDs. A general lack of quota raised the price of all rare earths, but the lightest and most common rare earths saw the most dramatic price increases.

It has been said that nothing cures high prices like high prices. And lately, this has been the talk of the rare earth industry. In the past few months, prices have been falling quite dramatically, both within and without China. The drops in price have been most dramatic for the lightest and most common rare earths outside of China. While various sources have named all manner of responsible parties, including "speculators", the anecdotal evidence from within China suggests that the market is simply very slow. That suggests that the likely culprit is demand destruction; companies are simply not buying the amounts they used to buy, due to high prices. The Chinese rare earth industry, which is consolidating into the hands of a few trusted players, is responding by suspending production, and the likely effect will be that prices will swing upwards when restocking is required. But the key question becomes how much restocking will actually be required; is this demand destruction permanent?

The short answer is, we believe, no. For example, catalyst makes such as W.R. Grace use lanthanum in products that improve the efficiency of petroleum refining, called FCCs. Grace management has publicly stated that, at what they were paying for lanthanum, their new rare-earth-free FCC formulations were cheaper for customers and still made more money for Grace. But if and when the price of lanthanum falls, the cheapest and most profitable way to make FCCs will, once again, involve lanthanum, and lanthanum demand should rebound.

Automobiles such as the Toyota Prius have been incorporating compact, lightweight and efficient electric motors using magnets made with boron, iron and a rare earth called neodymium in their hybrid vehicles for some time. However, Toyota also recently revealed that their new RAV4 Electric would be made using a drive train designed by Tesla Motors that uses a motor design containing no rare earths. It is possible to build such motors, but in private almost every automotive engineer will admit that a motor design using rare earths is lighter, smaller, more efficient and actually less expensive on a system basis at even the highest prices of neodymium we have seen. The real problem is that with Chinese quotas in place, not being sure you can purchase the materials means that you cannot use them in your design. Give the automobile designer guaranteed access to rare earths, though, whether they come from China or not, and you will see them readopt rare earths.

Wind turbines can also be made more reliable by incorporating generators using the same rare earth-based magnets mentioned above. But here they face two problems. A three mega-Watt wind turbine generator can use two tons of magnet, and that is a lot of material if you are not sure you can source it. And wind companies widely acknowledge that if the price of neodymium rises to near $100 a kilogram, it is no longer economic for them to consider its use. At its peak price not that long ago, neodymium was selling for $300 per kilogram. Make it available and make it cheaper, and wind turbines will be a serious long-term consumer of rare earths.

All the above should convince any reader that rare earths are not irreplaceable or critical. They are nice to have, if the price is right and especially if supply can be guaranteed. Fortunately, quite a few companies are working to guarantee supply outside of China. They may even do it too well. China's quotas, plus excess production by licensed producers and unlicensed production by a few mines allows about 120,000 tons of rare earth oxide production per year. We know where the production comes from, and we know the characteristics of those deposits. The result is that China can supply a total of almost 80,000 tons per year of the most common rare earths, lanthanum and cerium oxides, to the world.

Even when the Chinese export quota was 35,000 tons per year, no one was complaining about shortages. It was only when the quota was less than 30,000 tons a year, in 2010, that shortages loomed and we all became aware of rare earths. So, let's assume something silly for a second, that prior to 2010 all of the exports from China, let’s say 35,000 tons per year, was lanthanum and cerium oxides. Can companies like Molycorp, Lynas and Great Western Minerals Group supply enough of those materials to keep everyone happy?

The answer is emphatically yes. At the end of their phase II expansions, Molycorp will be providing as much as 43,000 tons per year of rare earth oxide. Lynas plans to make 22,000 tons. Great Western, or GWG as it is usually known, plans to produce 10,000 tons. Most of what all three of them make will be lanthanum and cerium oxide. In total, those three companies alone will make more than 57,000 tons of lanthanum and cerium oxide every year. Chinese companies likely won't stop selling those products, either. At their peak, lanthanum and cerium oxide sold for $150 per kilogram in the summer of 2011. Historically, those materials sell for less than $5 per kilogram. We have predicted that prices will drop to less than those historical levels, because of oversupply.

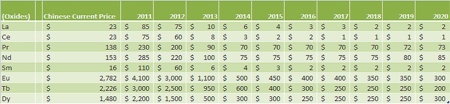

Similarly, we have projected supply and demand for a number of the most economically important rare earths, which also happen to be the ones where we have enough data to determine what prices might do given projected surpluses or shortfalls. We have also incorporated the effects of new technologies that reduce the demand for critical and truly rare heavy rare earths, such as dysprosium, in making powerful magnets that can continue to function at high temperature. Finally, we have incorporated the supply impact of new types of rare earths deposits that are inexpensive both to develop and to harvest. The result is our latest price deck for rare earths through to 2020.

Exhibit 1 – Byron Capital Markets Rare Earth Oxide Price Projections

It is important to note that this deck is, we believe, conservative. So even where we suggest that some companies may be overvalued, it is possible we are simply being pessimistic regarding their prospects. But we find quite a few stories that are overlooked and undervalued, in our estimation, and this using the very same price deck. It would seem to us that those names are the best investments remaining in the rare earths space.

While some of the hype may be over, some of the air may have been let out of the stock bubble in rare earths, we note that the industry itself is just beginning to grow. There is room for perhaps five to seven winning companies outside of China. And investors have a chance to grow their money with those potential winners.

Jon Hykawy is head of global research and clean technologies and materials analyst for Byron Capital Markets. He will speak during the Hard Assets Rare Earths Investment Conference in San Francisco on Tuesday, Nov. 29.