Shale gas changed everything.

Using hydraulic fracturing (or hydro fracturing) technology, North American gas producers over the past decade have unlocked trillions of cubic feet of new, unconventional gas reserves from shale.

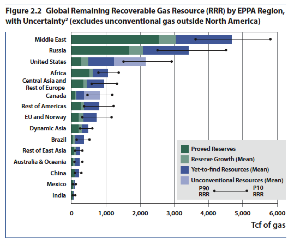

Check out the chart below from a recent study by MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Both the United States and Canada have seen big jumps in gas reserves due to unconventional resources. The majority of which is shale. In the U.S., this has added nearly a trillion cubic feet (tcf) of resource. In Canada, it's added about 500 billion cubic feet (bcf). These are huge adds.

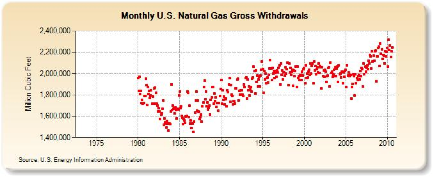

Shale has also been a big boost to production. U.S. natural gas (nat gas) output has taken off since 2006 as shale plays like the Haynesville, Marcellus and Eagle Ford have come online. Monthly nat gas output has risen 15%, from about 2 tcf per month to around 2.3 tcf—the first substantial rise in production since the early 1990s.

The Price of Success

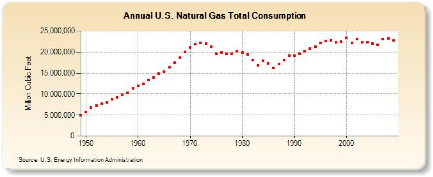

Of course, more production means, well, more gas. And even as new supply has come online in the U.S., gas demand remained relatively flat.

One of the major challenges for gas demand has been declining use by the industrial sector. Industrial demand accounts for 30% of ex-plant gas use in the U.S., the second-biggest demand source after electrical power.

And yet industrial gas use is falling. The sector's gas demand had been declining mildly up until 2005. In 2008, it appeared industrial use might be recovering; but the global financial crisis and recession kicked the sector in the teeth. In 2009, industrial gas use came in at a record low 6.1 tcf—down 25% from the 8.1 tcf used in 2000.

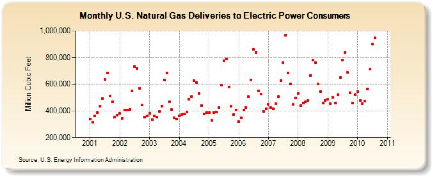

Other sources of demand, such as home heating, have remained relatively steady. One factor keeping gas demand somewhat buoyant has been consumption for electric power. With prices low, gas has become the fuel of choice for power generators.

Total demand for power came in at a record 6.9 trillion cubic feet in 2009. In August 2010, gas demand for power hit 949 billion cubic feet—just slightly below the all-time monthly record of 969 bcf, set in August 2007.

The upshot? Overall demand has struggled to hold firm even as the market has been flooded with new supply from shale.

The Warehouse Problem

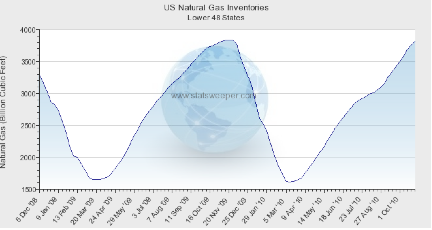

The U.S. is struggling to find a home for all its new gas production. In fact, low prices have prompted many producers to store their gas rather than sell it, hoping for better prices down the road.

With producers injecting large amounts of gas into storage, inventories swelled. In 2009, working gas in storage hit a record 3.8 trillion cubic feet—up significantly from the 3.5-bcf storage level that prevailed in the previous three years.

This year the song remains the same. With cold weather in the first months of 2010, America actually managed to draw down most of the record inventory build. But in April, gas began flowing back into storage. Strong demand during the summer air-conditioning season looked like it might dent this year's inventory growth. But since September, stockpiles have once again been accreting rapidly. In the week ended October 29, working gas in storage again topped 3.8 tcf.

Why All the Drilling?

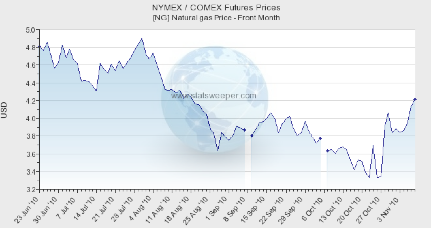

The new world of gas supply and demand has not been kind to prices. On July 3, 2008, front-month NYMEX natural gas traded at $13.58 per MMBtu. On September 3, 2009—just 14 months later—the price rang in at $2.51. A phenomenal 80% fall.

The onslaught has continued this year. Winter heating demand managed to lift front-month prices as high as $5.50 early in 2010. But the rally was small and short-lived. By October, prices fell back below $3.50.

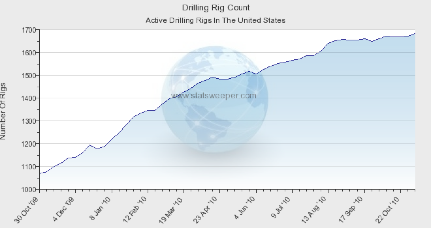

With over two years of falling prices behind us, many analysts have suggested "low prices should cure low prices." With producer profits low, gas drillers should simply stop plugging new wells, which would help curb supply and bring the market back into balance. But the fall in drilling hasn't materialized. Even as gas prices fell through 2010, the U.S. drilling rig count rose by more than 30%. Over the last two months, the count has flattened off but certainly not declined.

Why? A few reasons. . .Some gas producers were foresighted enough to hedge production when prices were high. Many of these were able to sell gas at $8–$10/MMBtu, even as futures prices were running half that. Drill away.

Those hedges are now falling off. But there are other incentives for producers to keep drilling. Leasehold obligations, for example. Acreage in U.S. shale plays has become a hot commodity. Every company wants to bank as much land as possible, as these plays comprise one of the main areas where producers see organic growth over the coming decades.

But holding land often means drilling. Landowners want to see production come online so they can start getting royalty checks. Few people are willing to let a would-be producer sit on acreage waiting for higher prices, which means many producers are drilling without any regard for the gas price. They could be losing money on today's wells and they would still do it. Winning the land grab is simply too important for the future.

Getting Liquid

Also preventing a falloff in drilling is the fact that gas isn't the only valuable thing you get from a gas well. Several North American gas plays also produce significant amounts of natural gas liquids (NGLs). NGLs have heavier hydrocarbons that are gaseous in the ground but condense to liquid when brought to the surface.

Nat gas liquids often sell for prices in line with prevailing oil prices. In fact, in places like Alberta, condensate can actually sell at a premium to light oil because the stuff is needed to dilute heavy oil from the oil sands for transport through pipelines.

Because of the value discrepancy, many gas producers have shifted their focus to liquids-rich plays. One of the leading ones is the Eagle Ford Shale of Texas. With Eagle Ford wells producing tens of barrels of liquids per million cubic feet (mcf) of gas, the economics on these wells are favorable even at current gas prices.

Some projections show that Eagle Ford producers could give their gas away for nothing and still make a positive return on shale wells selling the liquids. Across the liquids-rich sections of this play, returns on drilling investment can be as high as 200% at $4 per million British thermal unit (MMBtu) gas, according to Colorado's Bentek Energy. The break-even gas price for such wells is an astonishing $2.04.

Producers lucky enough to have a liquids kicker are doing fine at current prices. Keep those drills turning.

Move It on Out

So, if North American gas producers are going to keep producing (probably) and domestic demand is going to remain subdued (likely), is there any hope for nat gas prices?

Yes. The rest of the world.

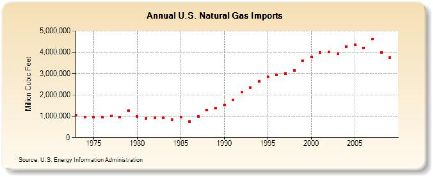

Before the shale gas revolution, everyone assumed America would be a serial importer of gas. The numbers bore this out. U.S. nat gas imports grew rapidly between 1985 and 2000, jumping from 1 tcf–4 tcf per year.

After a brief plateau in the early 2000s, it looked as if imports would continue to rise. By 2005, imports had jumped to 4.3 trillion cubic feet. And in 2007, America bought a record 4.6 trillion cubic feet of foreign gas.

Then everything changed. The combination of rising shale production and anemic demand suddenly put the brake on imports. In 2008, imported gas fell below 4 tcf for the first time since 2003. And in 2009, imports dropped again to 3.75 tcf—the lowest level since 1999.

Suddenly, America had something unthinkable—a surplus of gas. This led some producers and shippers to consider an equally radical solution—exports.

The Oil Link

That's because not every country on the planet is seeing low gas prices. In fact, in markets like Asia, gas prices have remained relatively buoyant.

Some U.S. producers have been able to take advantage of this arbitrage by sending gas to markets abroad in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG)—cooled, compressed gas that can be moved by ships.

LNG has been a lucrative business. In August, U.S. companies shipping LNG were getting an average price of $13.19 per MMBtu. Over twice the prevailing NYMEX price of $4.22 during that month. In fact, since late 2008, U.S. LNG export prices have consistently run at least 50% higher than domestic prices.

How come?

One of the major reasons is the oil price. In North America, natural gas prices are set in a stand-alone market where buyers and sellers determine the going price. Not so in many other parts of the world. Places like Asia and Europe still largely use an oil-indexed pricing system for gas. In the simplest schemes, gas is priced as a fixed percentage of the oil price. Under newer systems, gas and oil prices are linked by complex formulas known as S-curves.

The end result: Higher oil prices mean higher gas prices. And with oil having been near $80 per barrel for most of the past year, oil-linked gas prices abroad have been much healthier than North American market-based prices.

Because of this arbitrage, it makes sense for American producers to sell gas overseas rather than at home. In fact, analysts at PFC Energy (a Washington-based market research firm) estimate that at $80 oil, NYMEX prices would have to reach $8 per MMBtu before it would be economically advantageous for producers to sell gas in America rather than abroad.

If You Build It

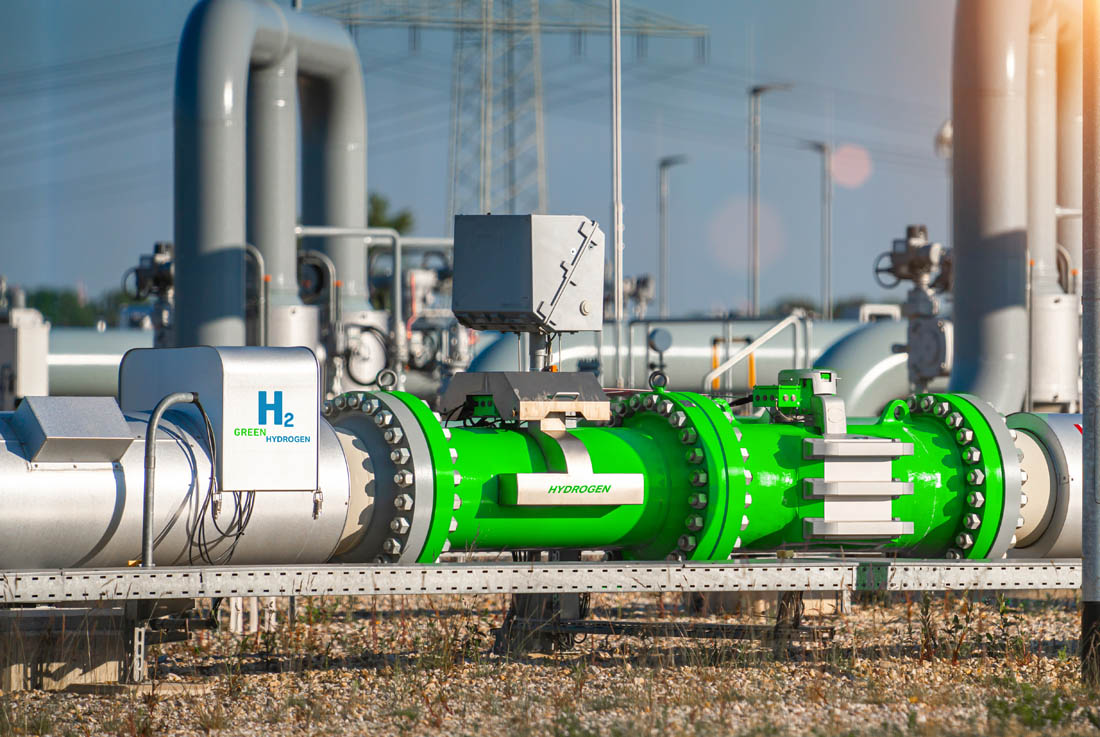

LNG export sounds like an easy solution for U.S. gas producers. But there's one problem—America has almost no infrastructure for exports.

Because everyone expected the U.S. to be a major gas importer, most existing LNG facilities in the country are designed to receive nat gas, not ship it out. At the peak in 2007, the U.S. was receiving nearly 100 bcf of gas monthly as LNG imports. By contrast, monthly exports of LNG have never totaled more than 8 bcf.

There simply isn't the export capacity to ship American gas abroad on any kind of meaningful scale.

This is changing, but slowly. In September, Cheniere Energy Partners L.P. (NYSE.A:CQP) was granted permission by the U.S. Department of Energy to export up to 785 billion cubic feet of LNG yearly from the company's Sabine Pass LNG Terminal in Louisiana.

Petroleum major Apache Corporation (NYSE:APA) is also trying to construct a LNG export terminal in Kitimat, British Columbia. This facility would ship up to 250 billion cubic feet yearly, sourced from northern British Columbia and Alberta where a number of shale gas plays are also hitting their stride.

Other than that, few new export facilities are on the horizon. Opposition to such projects has been strong from environmental groups and local residents concerned about safety. This has led to long permitting times, slowing the addition of new export capacity.

Over the long run, new facilities will get built, and this represents one of the best hopes for North American producers. Increased exports would help access higher prices, drain off surplus gas and, eventually, bring supply and demand more into balance.

The Benefits of Cheap Gas

Another light for North American producers could be new sources of demand. Last month, Morgan Stanley released a report showing that cheap gas in the U.S. will be a major boost to the petro-chemical industry. Because of prevailing low gas prices, American polyethylene producers will enjoy input costs 50% below their competitors in Europe and Asia as of 2012.

These are big savings. And a major incentive for companies like The Dow Chemical Company (NYSE:DOW) to build new production capacity in America. If the U.S. does become a 'petro-chemical haven,' the growing production base would be a major new source of gas demand, helping take some of the slack out of the market.

The other sector that loves cheap gas is utilities. With gas prices falling, power generators have been switching to nat gas wherever they can. In July, gas use for electricity generation hit an all-time high of 923 billion cubic feet. So far in 2010, gas use for electricity has run 4.3 tcf—more than 7% higher than the same periods in 2008 and 2009.

With growing opposition to "dirty" coal-fired power, utilities are already eyeing switches to nat gas. And the attractive U.S. gas price gives them one more reason to do so. This means gas-fired facilities may be the "weapon of choice" for new developments going forward. If so, this sector could also ramp-up demand significantly.

It All Comes Back to Shale

There's one thing that could throw all of these arguments out the window—shale gas going global.

The shale drilling technology that caused such upheaval in North American gas markets is now being taken on the road.

European shales have been a major focus for producers like Exxon Mobil Corp. (NYSE:XOM). Earlier this year, Halliburton Co. (NYSE:HAL) completed the first-ever hydro fracturing of a shale well in Poland. Companies have also been staking acreage in Germany, Hungary, Romania and the UK.

And Europe isn't the only frontier for shale. Malaysian state petroleum company Petronas said last month that it is investigating unconventional gas opportunities in Asia. Apache recently announced intentions to drill a shale test in Argentina. And even Saudi Arabia is reportedly interested in trying out shale gas technology on the oil-rich nation's large shale packages.

Of course, we have few results from any of these programs at this point. And success in new shale gas arenas will come down to more than just geology. It's also a game of costs.

One of the main reasons shale worked in North America was the services sector. Intense competition among drillers, completion experts and infrastructure builders drove down costs to the point where producers could make money tinkering with new shale plays.

This isn't the case in many other parts of the world. Shale gas completions are complex, technical tasks. This requires top people running the drills, pumps and mud logs. But getting top people and equipment into new locales is costly. Meaning flow rates have to be that much higher in order to yield positive project economics.

New shale successes, when they do come, will be in places where producers manage to optimize services, quality and costs. This will take time, and it won't happen everywhere.

But when new plays do stick, the impact on gas markets will be significant. There are trillions of cubic feet of gas in shales globally. This represents a major new source of supply wherever it can be unlocked with technology. Such developments would once again shift the dynamics of the world gas market. Keep watching this space.

Dave Forest is a professional geologist and has worked in the oil/gas, mining and environmental sectors for a decade. He previously managed the energy research division at Casey Research LLC, an American-based firm advising a worldwide client base on investments in the natural resource sector.

Dave writes Pierce Points, a free daily e-letter covering global natural resource trends and is a presenter at investment conferences across North America. He currently serves as chief operating officer of Sunward Resources Ltd., a Notela Group company and much of the research data he employs is derived from Statsweeper.

Want to read more exclusive Energy Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you'll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Expert Insights page.

DISCLOSURE:From time to time, Streetwise Reports LLC and its directors, officers, employees or members of their families, as well as persons interviewed for articles on the site, may have a long or short position in securities mentioned and may make purchases and/or sales of those securities in the open market or otherwise.