As the Dow was plummeting from 14,000 to less than 12,500 (nearly an 11% haircut), gold was also dropping, though not so steeply. The metal fell from a high of $683.50/oz on July 20 to an intraday low of $640 on August 16, a decline of 6.4%.

For a while, the correlation remained tight as investors rode alternating waves of optimism and pessimism about stocks and gold. Equities up, gold up. Equities down, gold down. Set your watch.

This correlation was due to a number of factors.

For example, the need for hedge funds and other institutions to sell anything with a bid – for instance, gold – in the scramble to build liquidity in suddenly (and surprisingly so) illiquid bonds and commercial paper.

Pressure on both equities and gold at the time can also be attributed to the dawning realization that (a) the credit crisis was real and, (b) it probably wouldn’t be terribly helpful to the global economy. Of course, when one worries about recessions and such, one thinks less of holding either stocks or gold. The former for the obvious reason that bad economic conditions make for bad business; the latter because anything that is supposed to be an inflation hedge can’t also be a deflation hedge, can it?

Though admittedly impatient to see the gold show get on the road, we were largely unconcerned by gold’s behavior. That’s because our eyes remained firmly fixed on the perfect trap set over the years for Bernanke’s Fed.

Like hunters of antiquity watching large prey grazing toward a large covered pit, the bottom of which is decorated with sharpened sticks, we watched the handsomely attired and well-groomed Bernanke and friends shuffle ever closer to the edge, their attention no doubt occupied by pondering the flavor of champagne to be served with the evening’s second course.

One minute pondering bubbly, the very next standing, wide-eyed and hyperventilating, on thin cover with decades of fiscal abuse cracking precariously under their collective Italian leather loafers. We can’t entirely blame Bernanke for the dilemma he now finds himself in; it was more about showing up to work at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Regardless, all of a sudden the Fed and many of the world’s central bankers found themselves faced with the rock-and-a-hard-place scenario we’ve been warning readers of for some months now.

Namely, raise rates – or even just do nothing – and the whole shaky structure of debt comes crashing down, pulling the global economy with it. Swing in the opposite direction by cranking up the printing presses to full speed and risk alienating foreign holders of an unprecedented six trillion in U.S. dollars, triggering a monetary crisis, also with global implications.

When Push Comes to Shove…

Watching the closely correlated moves between gold and the broader stock market in the early days of the crisis, however, had us wondering just when it would be that other purportedly intelligent market observers would figure out the nature of the Fed’s dilemma, and the inevitable implications of same. To wit, that when push came to shove, the Fed would almost certainly sacrifice the dollar.

The reasons for that conclusion are, at least in our thinking, obvious.

While the Fed and the world’s central banks could, after the initial round of rate cuts and cash infusions, switch course again and decide to simply sit tight, allowing a deep recession – or perhaps even a depression of 1930s depth – to clear out the monumental excesses now in the financial system, we don’t think they’ll find that option attractive, especially in the midst of a presidential election cycle. Instead, the law of relative unpleasantness strongly skews the odds in favor of the printing press option.

Specifically, they are now well aware of what sort of unpleasantness will almost certainly occur if they fail to feed the beast with greenbacks by the helicopter load. Collapsing real estate prices, closing factories, soaring unemployment and, given the size of the problems, a clear possibility of things spinning seriously out of control from there. Returning to my earlier metaphor, we’re talking a sure trip onto the sharpened sticks below.

Against that probability, they have the possibility that, by setting the printing presses on high speed, the Fed might alienate foreign dollar holders who, theory has it, have as much to lose from a falling dollar as anyone. So, maybe, just maybe, the foreign holders will hold tight, preferring to see their many trillions depreciate by, say, 10%, rather than taking a deeper loss by heading for the exits en masse.

And that provides the Fed just the intellectual cover needed to do what is, after all, its default mode – depreciate the currency. For the truth of that observation, look no further than the fact that the U.S. dollar has lost over 96% of its purchasing power since the creation of the Fed in 1913.

But there are additional reasons for the Fed to opt for a loose money policy. To name one, the U.S. is in the aforementioned presidential election cycle. Foreign dollar holders don’t vote, but heavily indebted Americans do. For another, a weak dollar will help make U.S. manufacturers stay more competitive (hey, it worked for the Chinese!). Finally, a weaker dollar benefits the government by allowing it to pay down its many debts in depreciated dollars.

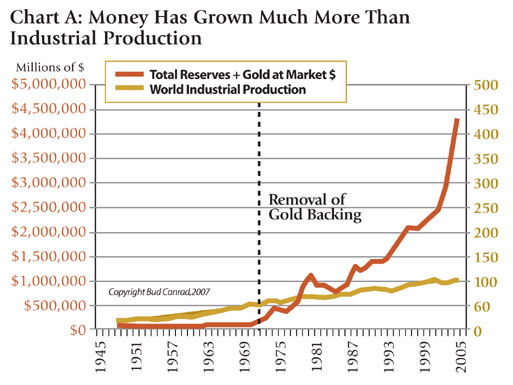

Most people don’t fully appreciate how poorly the Fed has managed the currency since cancelling the dollar’s convertibility into gold in 1971. That brazen act cut the ties between the dollar and any fundamental value, leaving only political restraint to underpin the dollar. The chart below paints a clear picture of the result.

In time, and maybe in our time, the piper has to be paid. And make no mistake, the price of too many dollars chasing too many goods is inflation. And record money creation leads to record inflation.

Of course, there are many potential negatives associated with a collapsing dollar, including the higher interest rates the Fed is trying to avoid in the first place, but those negatives are more hypothetical at this point than the clear and present danger of simply letting the global economy take it hard on the chin by staying out of the mess.

Given the choice between the possibility that foreign dollar holders will dump their greenbacks and disadvantage themselves in the process, versus the certainty of deep financial pain should the Fed do nothing at this juncture, we think the Fed will continue to take the path it believes is relatively less unpleasant and keep the spigots open wide on money creation.

Awakening Day

The market finally seemed to see the light on Thursday, September 6, when a major divergence in the paths of gold and the broader stock markets occurred. On that day, the Dow dropped over 125 points while gold shot up more than $13 an ounce. And it continued up on Friday, Monday and Tuesday, with gold breaking through the $700 mark even as equities did little or nothing. That was the first time the two marched to different drummers since the crisis hit.

Since then, gold has gained a new appreciation in the investment milieu. When the stock market soared after the Fed lowered interest rates, so did gold. And when the market retraced, gold pushed higher still.

Even more cheering for readers of our monthly editions of BIG GOLD is that the market didn’t just come to its senses about the role that gold had to play in the unfolding crisis, it also remembered that gold stocks were, in fact, related to gold.

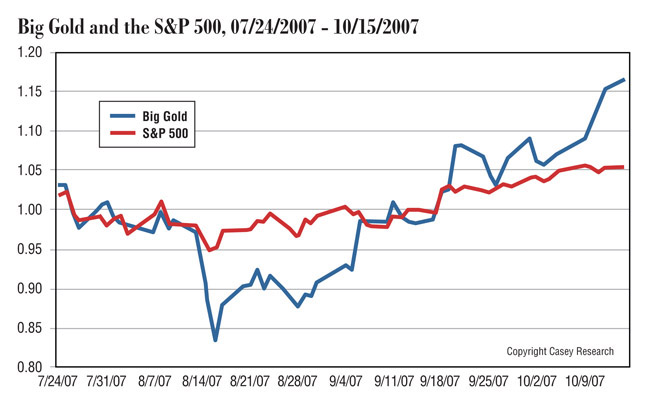

The chart below shows the action in the BIG GOLD portfolio of recommended securities from the period of August 15 – October 15, 2007. As you can see, until the first week of September, the Big Gold portfolio had been tracking, or even underperforming, the broader market as represented by the S&P 500.

While still baby steps in terms of what we expect, this is exactly the sort of price action we’ve been expecting… an early indication that institutional investors are starting to move into large-cap gold stocks, the investment class that pops first to mind when the Wall Street crowd decides that gold belongs in the portfolio.

No matter which way things go, gold – as it has been for thousands of years – is the ultimate hedge in times of crisis. And the recent shift into the metal, and now to gold stocks as well, is a sign that increasing numbers of investors are learning to see it as such.

David Galland is the managing editor of the BIG GOLD advisory from Casey Research, one of the nation’s oldest and most respected organizations providing unbiased research on natural resource investments.

BIG GOLD is designed for conservative investors looking for an easy and lower-risk way to participate in gold markets through producing and near-production precious metals companies, ETFs and mutual funds you can buy and sell through your favorite discount broker.

Consider: Since its low in 1999, the price of gold bullion is up about 200%. By comparison, the American Stock Exchange index of gold stocks is up 556% in the same bull market phase! That's profit-boosting leverage of better than 2-to-1... financial rocket fuel.

To learn how you can play the gold bull market without taking excessive risk, learn more about BIG GOLD and its 3-month 100% money-back guarantee by clicking here now.